On April 4, 1953, the Turkish submarine sank within the Canakkale Strait after colliding with a Swedish cargo ship. Only 5 of the 86 sailors on board survived after rescue efforts failed to achieve the sunken vessel.

This month marks the Turkish army’s lethal marine accident within the Canakkale Strait, a traditionally strategic location the place the Ottoman Empire, the predecessor state to Türkiye, landed a shocking defeat to the Allied armies throughout WWI.

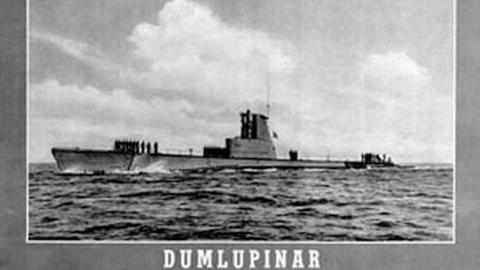

Seventy years in the past, TGC Dumlupinar was on the return journey from the Mediterranean Sea, the place it had taken half in a NATO coaching train alongside TCG Birinci Inonu (S330), one other Turkish submarine. The two vessels have been heading to the Golcuk port within the Marmara Sea, the place the headquarters of the Turkish Navy have been situated.

But heavy misty climate protecting the strait, the scene of numerous battles and voyages, would fatefully hamper Dumlupinar’s voyage on the darkish night time of April 4.

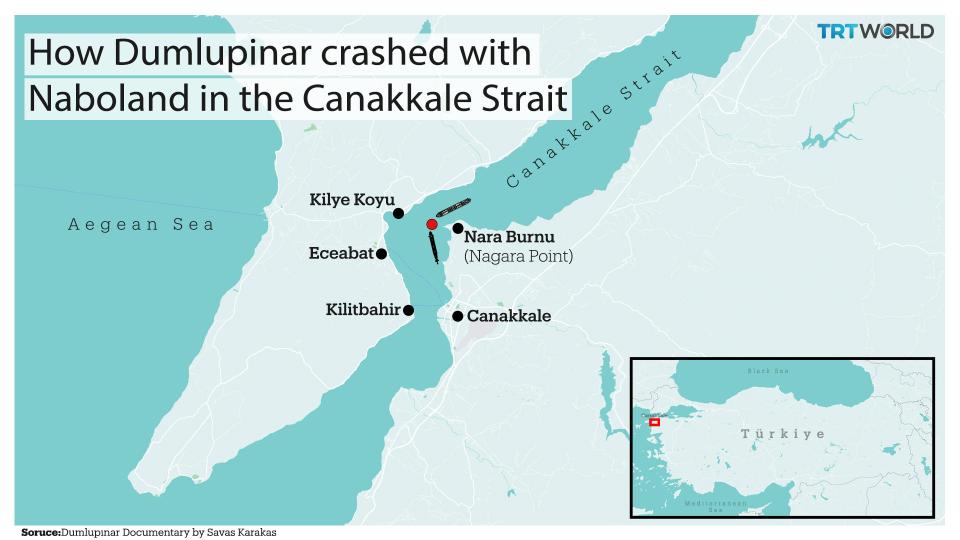

At round 2 am, because the submarine approached Nara Burnu or Nagara Point, one of many deepest and narrowest factors of the Canakkale Strait identified for robust currents, a Swedish cargo ship, MV Naboland, all of a sudden emerged from a blind flip and was on the identical monitor because the Turkish vessel.

“As Naboland was turning around Nara Burnu at a speed unusual for a waterway passage, the ship slid inward of the strait and went into Dumlupinar’s lane, leaving little space for the Turkish submarine to safely surpass the Swedish vessel,” says Ercument Ozmen, a retired senior chief petty officer on the Turkish navy and an knowledgeable on the Dumlupinar catastrophe. Ozmen served as a radar operator at TGC Murat Reis, a Turkish submarine, for almost twenty years.

“If Dumlupinar stayed regular, it could have hit Naboland head-to-head.”

Amidst the nerve wracking ordeal, Ozmen added, Dumlupinar’s leading officers made an announcement that the submarine will move to the right near the eastern shores of the Canakkale Strait.

But if Dumlupinar had steered too far to the correct, it could have hit the shore. The submarine was caught between a rock and a tough place, Ozmen explains.

(Fatih Uzun / TRTWorld)

The fateful determination

Hearing the announcement, Sabri Celebioglu, Dumlupinar’s commander, climbs onto the deck from his cabin to personally oversee the scenario. Celebioglu thought taking the correct flip would imply crashing into the shore, so he determined to maneuver to the far left of Naboland close to the western shores of the strait in a bid to keep away from a collision with the Swedish vessel, says Ozmen.

But the submarine was racing in opposition to time within the extraordinarily slim strait. Although it accomplished its flip in the direction of the left, it couldn’t escape the incoming Swedish cargo ship. Soon after, a head-on collision occurred.

Many army consultants consider that at this second, it could have been a better option to show the ship utterly to the correct though it may presumably be stranded on land, as an alternative of turning the ship to the left, says Ozmen.

Eight sailors standing on deck fell into the ocean because of the sheer pressure of the collision. Two have been immediately killed by the Naboland propellers and one other drowned in chaotic circumstances, whereas 5 sailors scuffling with the Canakkale Strait’s strongest currents have been saved by the Swedish ship’s rescue boats and lifesavers. They have been later transferred to an area hospital by a Turkish customs ship.

The scenario under the deck was as dangerous because the occasions unfolding on the floor because the closely broken Dumlupinar was shortly descending in the direction of the seabed. The crash left the Turkish submarine with out electrical energy, severing most communication as water entered from the bow.

According to the Turkish defence ministry, some survivors of the catastrophe and consultants, together with Ozmen, 81 sailors misplaced their lives. Of the 81 deaths, three occurred on the deck in the course of the crash, whereas 78 died caught contained in the sunken submarine. As a end result, 86 sailors have been believed to be aboard Dumlupinar previous to the crash, based on each consultants and authorities.

While the 78 sailors caught within the submarine rushed to achieve the strict to safe their lives within the torpedo room, a lot of them didn’t make it beneath the growing stress of rising waters.

Only 22 sailors have been capable of attain and lock themselves within the stern torpedo part as Dumlupinar utterly sank on the Canakkale Strait’s deepest and darkest mattress after an explosion within the ship’s central compartment.

Some accounts recommend that in addition to these 22 sailors, a number of additionally quickly survived in different elements of the submarine. Ulvi Erhazar, a non-commissioned officer, was a type of surviving sailors who tried to achieve the floor by swimming from the sunken submarine, however he didn’t make it.

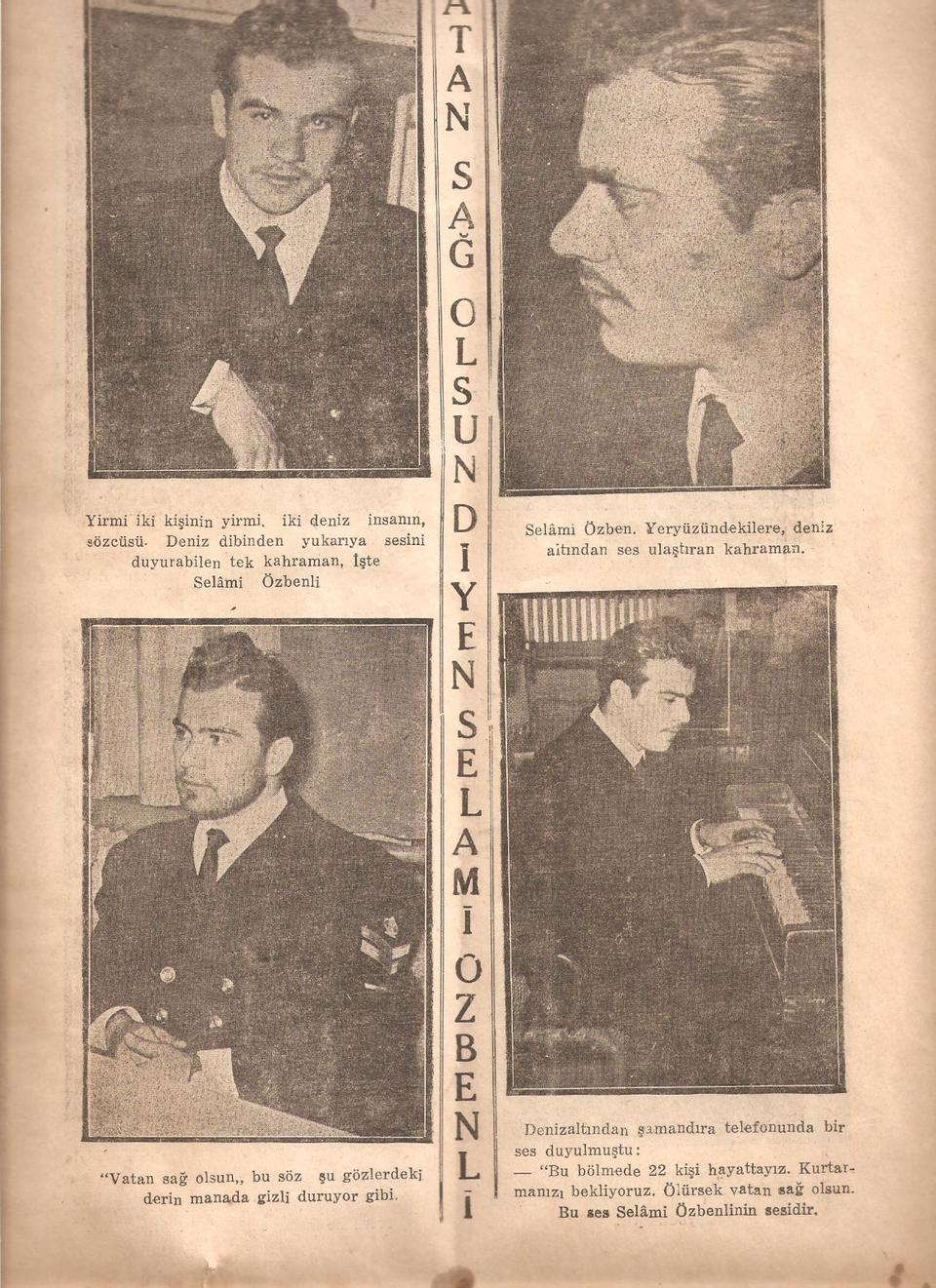

Selami Ozben, a petty officer, had despatched an emergency communications buoy to the floor to let the Turkish authorities know that there have been survivors contained in the sunken ship. But amid the darkish night time, the buoy was invisible to any close by vessel.

(Credit: Ercument Ozmen / TRTWorld)

When the solar rose, the Turkish customs ship, which had rescued 5 sailors the night time earlier than, was the primary to identify the communications buoy. Selim Yoluduz, the customs ship’s second engineer, had regarded for a phone contained in the floating buoy and noticed the inscription on the phone, which connects the buoy with the submarine via a cable.

“The submarine TCG Dumlupinar, commissioned in the Turkish Navy, has sunk here. Open the hatch to establish contact with the submarine,” stated the inscription on the phone. When Yoluduz picked up the telephone, he reached Ozben.

The Turkish authorities alerted naval forces, together with Kurtaran, Turkish for rescuer, a submarine rescue ship, to rescue the remaining 22 sailors. From the seabed, Ozben advised Yoluduz of the ship’s situation and the variety of surviving sailors within the part they sheltered contained in the submarine.

Yoluduz knowledgeable Ozben the place Dumlupinar had crashed with the Swedish ship and that they have been 90 metres under sea. He additionally advised trapped sailors {that a} rescue ship was on the best way to save lots of them from sure loss of life and that they might strive every thing to get them out alive.

Yoluduz had then handed the phone to Zeki Adar, the highest navy officer of Canakkale on the time. “My son, we will rescue you. Don’t worry!” Adar stated. “Thank you! Long live my country!” replied Ozben. After this dialog, a number of contact makes an attempt have been reportedly made with the sunken submarine survivors.

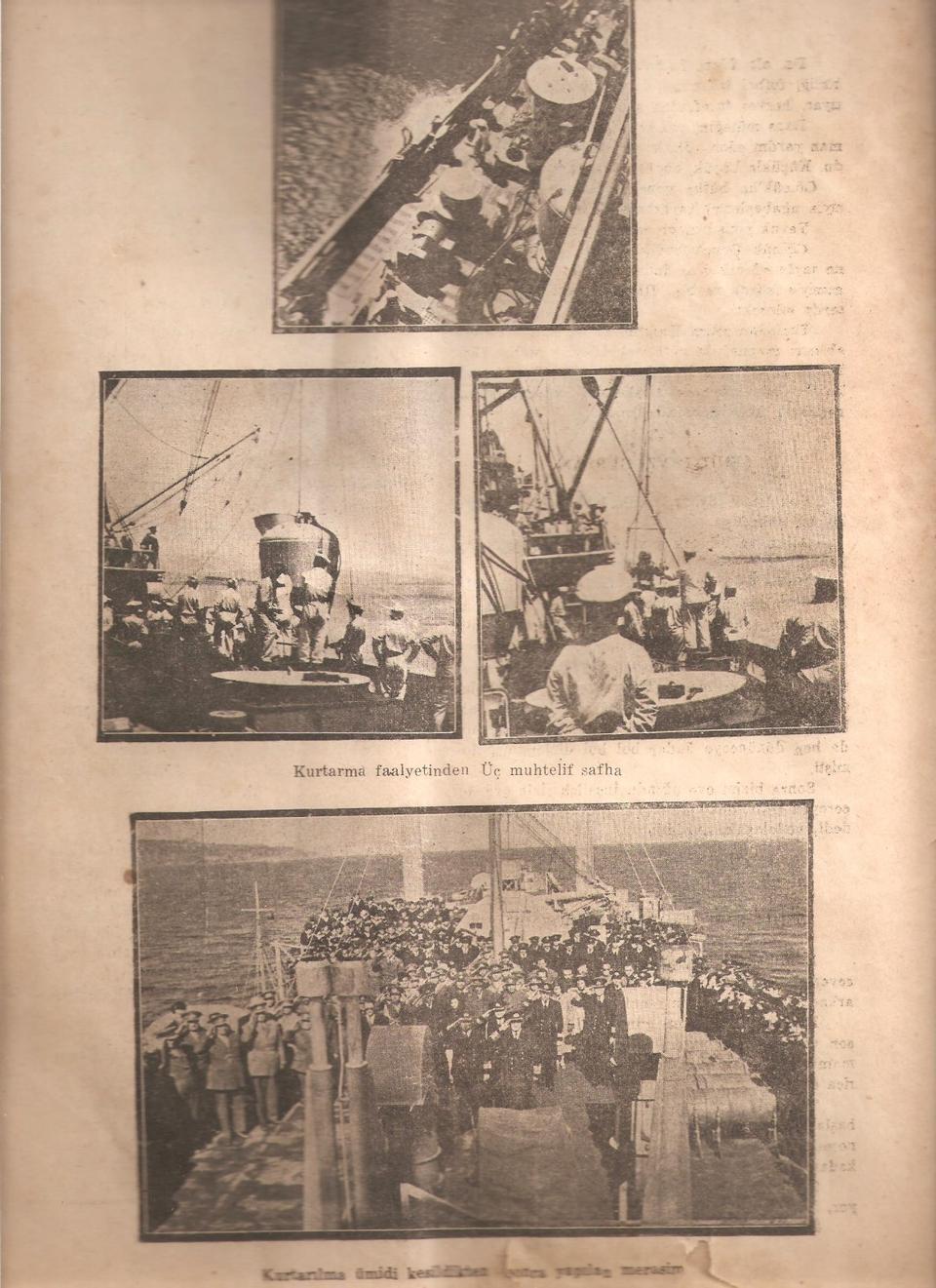

Kurtaran arrived on the crash website 10 hours later, however it could take one other 12 hours to position the rescue ship in a location parallel to the sunken submarine as a consequence of extreme climate circumstances and robust currents. Placing the rescue ship on the correct location near the submarine is at all times essential for submarine rescue operations.

As if that wasn’t sufficient, inside these 12 hours, a rope on board the rescue ship had severed the buoy cable, disrupting communication between trapped sailors and the floor.

(Credit: Ercument Ozmen / TRTWorld)

The greatest problem in the course of the tried rescue mission was getting the wires of the diving bell, a chamber used to move divers from sea floor to depth and again up, to the escape hatch of the older-fashioned submarine, which was a former American ship transferred by the US to Türkiye in 1950 to hasten Ankara’s entry to the Western alliance in 1953.

Unfortunately, robust currents and dangerous climate prevented divers from reaching the sunken ship to get the wires of the diving bell to the submarine’s escape hatch, says Ozmen. According to consultants, solely three days price of oxygen was most likely obtainable for 22 sailors and on April 7, rescue efforts ceased after 10 failed makes an attempt to dive in the direction of the submarine.

The similar day, the Turkish navy introduced that each one 78 sailors contained in the sunken submarine have been thought-about useless. The Dumlupinar incident was Turkish army’s most threatening naval maritime catastrophe, and the Turkish navy has since commemorated Marine Martyrs’ Day on April 4 every year in remembrance of the 81 victims of the catastrophe.

(Ercument Ozmen / TRTWorld)

Bad luck?

For centuries, sailors throughout totally different continents have believed that luck at all times performed a important function of their survival throughout their harmful voyages. “If a ship had an accident a short time after its launch, they would consider it a sign of bad luck. That ship is always considered unlucky from then on,” says Ozmen.

Interestingly, Dumlupinar, which was initially referred to as USS Blower earlier than the US gave it to Türkiye, had a nasty accident within the Pacific two months after it was commissioned by the US military in August 1944.

Even after that, the USS Blower had had quite a lot of accidents throughout its commissioning beneath the US military, based on Ozmen.

Running a 20,000-tonne submarine is a really tough job, says Ozmen, who had gone via seven near-sink experiences, two accidents and lots of arduous occasions by which he had thought that his ship would go down throughout his lengthy profession. “The submarine is always trying to go down,” he says. As a end result, the submarine’s crew at all times want luck.

Perhaps one other dangerous omen is the ship’s identify (Dumlupinar is a district in Türkiye’s Kutahya province by which the Turkish military inflicted a last blow to the invading Greek armies in the course of the Independence War between August 26 and 30, 1922). Within the Turkish navy, three submarines bearing the identical identify had their justifiable share of bother.

Prior to the 1953 catastrophe, there was one other Dumlupinar, imported from Italy, which was in an accident near Istanbul’s Anatolian aspect in 1949 and was decommissioned.

A 3rd ship of the identical identify crashed within the Canakkale Strait in 1976. After being repaired in Golcuk, there was a fireplace onboard the ship. It returned to sea in 1978 however was decommissioned 5 years later.

“After this point, the Turkish navy made the decision not to name any ship Dumlupinar,” says Ozmen.

Mithat Atabay, an educational and author of a number of books on the Dumlupinar catastrophe and different submarine accidents, echoed the sentiment. “Unfortunately, ships named Dumlupinar were ill-starred ships for us,” Atabay tells TRT World.

Source: TRT World

Source: www.trtworld.com